Africa's Credit Revolution

- Jun 23, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 29, 2025

WHY THE NEXT LEAP IS DATA. NOT DOLLARS.

By Jay Nair, Managing Partner

Africa’s next credit revolution won’t be driven by cards or collateral—it’ll come from consented data and open banking. This article explores how digital footprints and mobile SIMs can become credit passports for millions like Amina, unleashing jobs, lending, and economic growth across the continent.

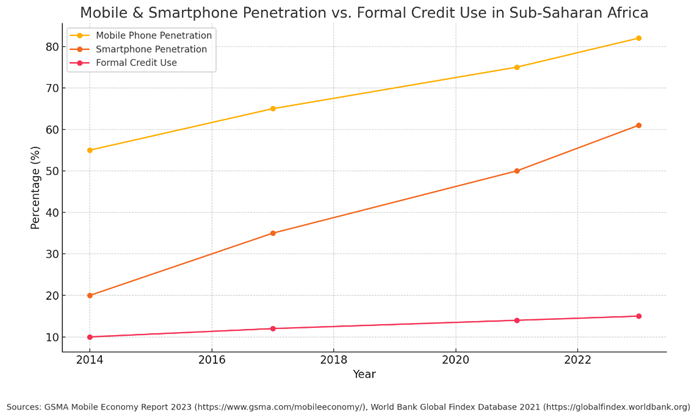

Across Africa, digital finance has leapt forward—but real credit access still lags behind. Mobile phones and digital wallets now reach hundreds of millions. Yet affordable, meaningful credit remains out of reach for most.

Open banking—securely connecting consumer-permissioned data from banks, wallets, telcos, and beyond—is Africa’s best shot at bridging this longstanding credit inclusion gap. Just as mobile phones leapfrogged landlines, and mobile money leapfrogged traditional banks, open banking can leapfrog credit access for the next billion.

It’s not just about finance; it’s about dignity, inclusion, and economic agency.

Meet Amina—and Her (Credit) SIM

Amina, a vegetable trader in Dodoma has no payslip, no formal credit history, and no fixed collateral. But she transacts over $400 a month through her mobile wallet, repays her wholesaler float daily, pays school fees digitally, and restocks weekly.

She is financially active—but to banks, invisible. But her digital trail, usually via her mobile SIM card, tells a powerful story.

Amina’s SIM is more than a connection—it’s a financial passport. It carries her mobile money transactions, airtime purchase habits, paybill activity, and even repayment patterns for nano-loans. Over time, it becomes a behavioural credit profile.

In short, it’s her Credit SIM—a portable, permissioned identity that can bridge the data gap and unlock formal lending.

Multiply Amina by millions—and you see the size of the opportunity. The SIM-as-passport model is not theory—it’s already happening, informally. Amina’s story is a blueprint for what structured, secure, and consented data-sharing could unlock.

From Financial Access to Credit Inclusion

Sub-Saharan Africa holds 17% of the world’s population but a meagre 3% of global private credit—$430Bn in 2022 versus over $155Tn globally.

Over 55% of adults in the region have financial accounts, many through mobile money. Yet in Tanzania, for example, while over 60% have accounts, fewer than 10% report borrowing from formal institutions.

The implication? Financial access has grown, but not credit access. This isn’t just a market inefficiency; it’s a developmental barrier. Without credit, micro-enterprises stay micro. Resilience remains fragile. Small businesses stay trapped in cash cycles.

Amina knows this. She can’t grow her stall without borrowing. She borrows informally or not at all. Her ambition has a ceiling imposed by lack of capital.

Credit Opportunity by the Numbers

Kenya’s MSME credit gap: $20–30B. Tanzania: $15–25B. IFC estimates Sub-Saharan Africa’s SME financing gap at over $330B.

Even modest inclusion moves the needle. If just 10% of Africa’s rising middle class, expected to reach 500M by 2030, accessed $50–100 in credit, that’s $2.5–5B in new loans.

IFC data shows that every $1M in SME credit generates 16.3 direct jobs over two years. In Sub-Saharan Africa alone, that is 40K-80K new jobs and $200-$400M in direct economic output—before accounting for indirect benefits, multiplier effects, or broader productivity gains.

That’s the power of smart capital directed toward entrepreneurs like Amina. It doesn’t just fund stalls—it fuels local economies.

Why Banks Struggle to Lend

Why do banks, despite their reach and capital, remain hesitant lenders?

First, data gaps: most borrowers lack formal credit histories, income documentation, or provable employment. Credit bureaus have patchy coverage.

Second, the predominant reliance on physical collateral for lending disqualifies vast swathes of the population who possess limited or no fixed assets.

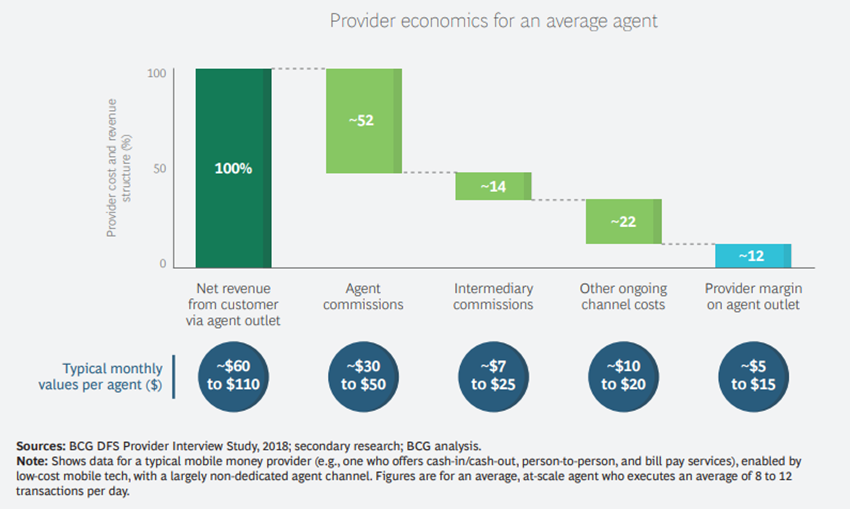

Third, high costs to serve. In many countries, banks use agents to reach customers. BCG notes these providers lose over 85% of revenue to commissions and operational costs—leaving just a ~12% margin, even in optimal conditions. Add regulation, provisioning, and tech costs, and the unit economics of small-ticket lending collapse—no matter how large the market.

Finally, regulation constraints. In Tanzania, for instance, MFIs are capped at 3.5% monthly interest (~42% APR). High in theory, yet often insufficient to cover risk for thin-file customers.

This is a vicious cycle: limited credit access discourages formal participation, which in turn reduces the data available to assess risk, making banks even more cautious.

Digital but Disconnected: The Mobile Paradox

Africa is digital. Mobile penetration topped 1 billion accounts in Sub Saharan Africa in 2024, and smartphone penetration during the same period was 72%.

Telco-based products like Safaricom’s Fuliza and M-Shwari in Kenya or Vodacom’s Songesha and Airtel’s Kamilisha in Tanzania offer nano-loans to millions. These rely on behavioural signals: airtime top-ups, utility payments, repayment patterns. That digital footprint, though narrow, is often more revealing than a payslip.

But these loans are small and can be expensive (often APR > 100% implied annualized). They’re great for emergency smoothing—keeping lights on, covering bills—not for asset growth or business scaling.

For Amina, these loans may help buy tomatoes—not expand her stall.

For millions of merchants and micro-entrepreneurs, this means continued dependence on cash, informal suppliers, and short-term cycles.

Credit SIM: The African Leapfrog

In markets where open banking has taken root — such as the UK, India, Australia — it connects consumers, fintechs and banks. In Africa, the leap is wider — connecting not just banks and fintechs, but telcos, wallets, SACCOs and the informal economy itself.

The SIM card, already near-universal, becomes the anchor. It contains not just identity (via SIM registration KYC) but digital behaviour: top-ups, remittances, bill payments, airtime credit repayments. Fintechs like Tala in Kenya, FairMoney in Nigeria are already using broader data—SMS, wallet history, phone activity—to underwrite loans.

Mobile data is powerful. But today, these data sets are fragmented, proprietary, and non-portable. Credit history doesn’t travel, even when consumers do.

Open banking solves this. It builds an ecosystem where consumers like Amina can share financial data across providers with consent. Her mobile payment history, utility bills, and inventory purchases become assets. She can share them with lenders—without switching platforms or reapplying from scratch.

In Tanzania, fintechs like Manka are prototyping this: aggregating mobile money records, bank statements, and utility transactions into a unified credit profile. Manka isn’t the endgame—it’s the blueprint for what’s possible.

How Open Data Makes Credit Work

First, data portability. Credit history follows the consumer. A merchant in Kumasi could share mobile money history, electricity bill payments, and inventory purchases with a lender in Accra or Lagos—with consent, instead of having their information locked within a single bank or mobile wallet.

Second, fairer scoring. Instead of relying solely on credit bureaus and collateral, open banking allows dynamic insights into spending, earning, and repayment—creating a richer, more inclusive picture of financial reliability.

Third, it drives competition and innovation. Lenders can build better and price smarter, knowing they’re not underwriting blind .

And fourth, it reduces defaults. Defaults thrive in opacity. Open banking brings transparency—and with it, accountability. Asset finance provider Watu’s recent 85% profit drop—driven largely by delinquencies—highlights the cost of weak credit infrastructure. Open banking would have allowed early warning signals and created accountability.

A Continent-Wide Opportunity

Nigeria has launched open banking. Kenya is drafting its framework. Ghana and Rwanda are moving. But without pan-African standards, progress is fragmented. Think of it like telco interoperability: Imagine if Safaricom users couldn’t send money to Airtel users. That’s today’s credit market.

AfCFTA and PAPSS are stitching together payments across the continent. Now it’s time to stitch credit.

Imagine Amina buying tomatoes in Dar, selling in Dodoma, and getting a loan from a Ghanaian lender—using a digital credit profile tied to her SIM and mobile behaviour.

Her SIM isn’t just a chip. It’s a passport to the formal economy—one that should work across borders. Linked to a secure identity, layered with consent, and plugged into open banking rails, it could unlock access to lenders who would once dismiss her.

This is not utopia. It is executable. It requires bold regulation, public-private coordination, and a mindset shift—from control to enablement. It will lower risk and cost for lenders, and catalyse a new era of trade finance, inventory finance and SME growth across the continent.

Development finance institutions (DFIs) have a critical role to play —funding public infrastructure like digital ID systems, API standards and supporting pilots that include traditionally excluded segments.

The Bottom Line

Africa’s credit revolution won’t come from collateral or cards—but from consented, connected data.

Open banking is the missing link, connecting the continent’s mobile-driven economy to smarter, fairer credit. That requires data mobility, not just money mobility. Smartphones, digital footprints, fintech innovation, and regulatory appetite already exist. Now we must connect them.

If just 10% of the unbanked accessed even $100 in credit, powered by open data and consent-driven access, it could unlock billions in new economic activity—and new livelihoods.

Just ask Amina in Dodoma. She pays her suppliers, school fees, and rent via mobile. With open banking, that behaviour becomes a credit score—and a shot at real growth.

“If they can see how I run my business through my phone,” Amina might say, “maybe they’ll trust me with a loan I can grow with.”

That’s the real promise of open banking: not just finance, but dignity. Not just platforms, but progress.

And the time to build it is now.

Comments